Financial Security. For Life.

Blog for Professors and TIAA Participants

Funding Retirement Plans to the Maximum

General Introduction

I want to persuasively convince anyone who harbors the least little doubt that saving money in a retirement plan is dramatically superior to saving money outside of a retirement plan. It isn’t a matter of opinion; it is mathematically provable. This blog will present our basic arguments and our summarized conclusions. We will also list the preferred order for making contributions to different plans and some details about specific plans. Please note that not all plans may be available at your place of employment. As with all of the posts in this blog, more details and specifics can be further researched in our book, Retire Secure for Professors and TIAA Participants (RSPT). Kindle & hardcover editions available on Amazon. Click here or visit https://a.co/d/04j2AT9n to get your copy today.”

The Math in a Graph

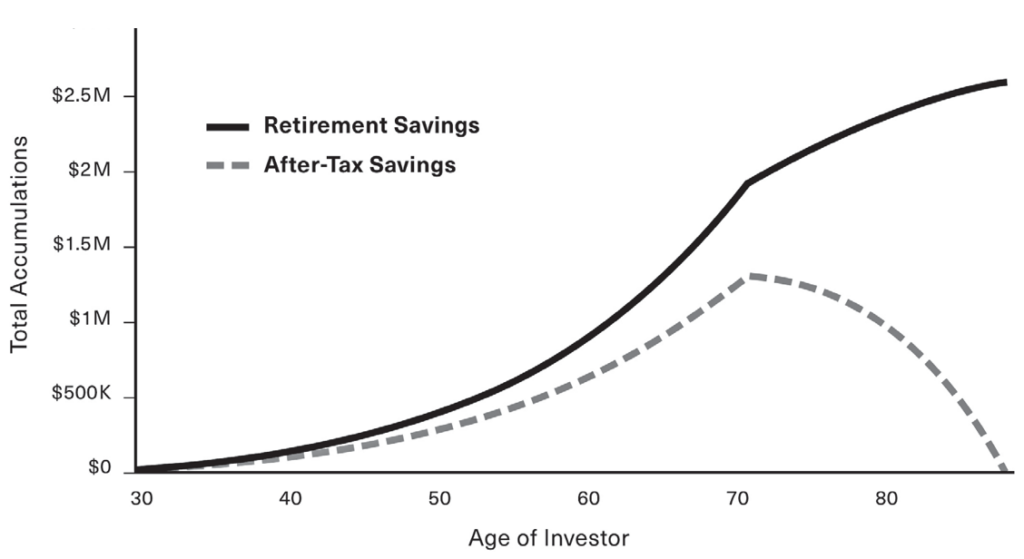

Let’s compare two basic scenarios

1. You earn the money, you pay the tax, you invest the money you earned, and you pay tax on the dividends, interest, and capital gains.

2. You earn the money and then invest money in your retirement plan, and you get a tax deduction. The money grows tax-deferred, and you don’t pay taxes on that money until you take it out.

Both scenarios begin with investing beginning at age 30, and contributions amount to $8,000 per year, indexed for inflation.

Retirement Plans and Tax-Deferred Savings vs. After-Tax Savings Accounts*

Detailed assumptions can be found by clicking here.

In the real world, not only is there a tax advantage to saving in a retirement plan but doing so builds in the discipline of contributing to your retirement plan with every paycheck. The example above assumes that if you are not putting the money in your retirement plan, you are saving and investing an amount equal to what your retirement contribution would have been. But can you trust yourself to be a disciplined saver? Will the temptation to put off saving for retirement until the next paycheck undermine your resolve? Even if you do put it in savings, knowing you have unrestricted access to the money, can you be confident that you would never invade that fund until you retire?

So assuming you trust our calculations (and if you need more details see Chapter 2 of RSPT), given reasonable assumptions and all things being equal, following the adage, “Don’t pay taxes now—pay taxes later” can be worth over $2 million over your lifetime. That sums up why we believe it is critical to invest in retirement plans to the max.

The Hierarchy for Investing in Available Retirement Plans

Here is the best order for contributing to the different types of retirement plans.

Subject to exception (determined by personal circumstances) and what is available to you:

1. Take advantage of any employer match.

2. Take advantage of a Health Savings Account (HSAs), if available to you.

3. Contribute to Roth IRAs and back-door Roth IRAs, subject to exception based on tax brackets.

4. Contribute to Traditional retirement plans or IRAs.

5. Contribute to nondeductible IRAs or nondeductible contributions to a retirement plan.

6. Save money in a plain old after-tax brokerage account.

Employer Matching Contributions

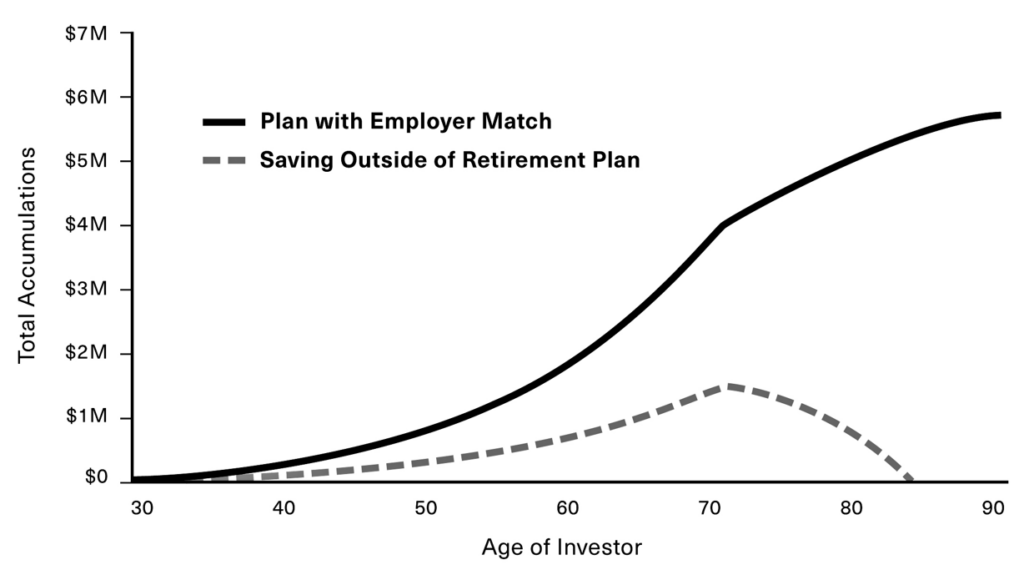

If your employer offers a retirement plan matching contribution, the cardinal rule is contribute at least the amount the employer university is willing to match—even if it is only a percentage of your contribution and not a dollar-for- dollar match. Matching contributions are most commonly found within 401(k), 403(b), and 457 plans. Many eligible 403(b) plan participants also may have access to a 457 plan. You can, in effect, enjoy double the ability to tax-defer earnings through participation in both the 403(b) and 457 plans. Even if your employer is only willing to make a partial match up to a cap, you should still take advantage of this opportunity.

What follows is a graph that uses the same basic facts of the first graph but adds in a 100% university matching contribution of $8,000.

Retirement Assets Plus an Employer Match vs. After-Tax Accumulations*

Detailed assumptions can be found by clicking here.

Broad Retirement Plan Categories

Generally, all retirement plans in the workplace fall into two categories: Defined Contribution Plans and Defined Benefit Plans.

In a defined contribution plan, each individual employee has an account that can be funded by either the employee or the employer, or both. In a defined contribution plan, the employee bears the investment risks. In other words, if the market suffers a downturn, so does the value of your investments. Conversely, if the market does well, you are rewarded with a higher balance.

At retirement or termination of employment, subject to a few minor exceptions, the money in a defined contribution plan sponsored by the employer represents the funds available to the employee that can be rolled into their own IRA. A list of common plans follows below.

In a defined benefit plan the employer contributes money according to a formula described in the company plan to provide a promised monthly benefit to the employee at retirement. Many people refer to these types of plans as “my pension.” The amount of the benefit is determined based on a formula that considers the number of years of service, salary (perhaps an average of the highest three years), and age.

In the private sector, defined benefit plans usually do not allow the employee to contribute their own funds into the plan, and the employer bears all of the investment risk. Please note, defined benefits plans are much less common currently, and they have widely varying benefit amounts, participation rules, and vesting schedules.

For people with defined benefit plans, there are few opportunities to make strategic decisions during the working years to increase retirement benefits. It might be possible to increase the retirement benefit by deferring salary or bonuses into the final years or working overtime to increase the calculation wage base. These opportunities, however, depend on the plan’s formula, and they are often inflexible and insignificant.

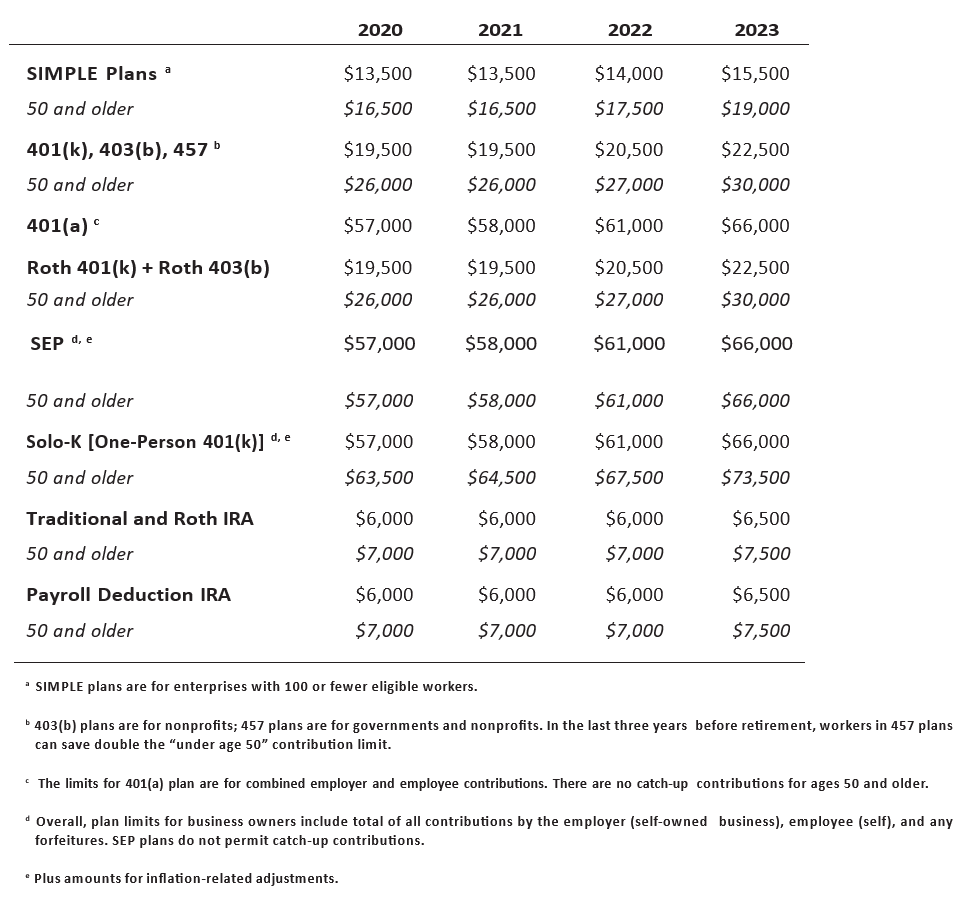

A List of Common Defined Contribution Plans and the 2023 Contribution Limits for Reference

Maximum Deferral Contribution Limits for 2021-2023

Please remember that, with the exception of the Roth accounts (discussed more fully in a future blog), every one of the retirement plans listed above works basically the same way. Subject to limitations, your taxable income is reduced by the amount you contribute to your plan. Your employer’s contribution is not subject to federal income taxes when it is made, nor is your deferral contribution. You pay no federal income tax until you take a withdrawal from the plan, and your money can only be withdrawn according to specific rules and regulations. Ultimately, the distributions are taxed at ordinary income tax rates. These plans offer tax-deferred growth because as the assets appreciate, taxes on the dividends, interest, and capital gains are deferred—or delayed—until there is a withdrawal or a distribution. For more details on any of the plans refer to Chapter 2 in RSPT.

How Many Plans are Available to You?

There is a good possibility that you have the opportunity to invest more money in your retirement plan or plans than you realize. For an extended example of a couple making multiple contributions to multiple plans please read the Mini Case Study 2.3 in Chapter 2 of RSPT.

Conclusion

You should contribute the maximum you can afford to all the retirement plans to which you have access in the order recommended in this blog. And remember, most professors have the ability to contribute more money to a retirement plan than they thought.

The next blog installment with look at good options for life insurance, which serves a critical function during the accumulation years.

If any particular topic catches your attention, remember a full discussion is available in our book Retire Secure for Professors and TIAA Participants, click here or visit https://a.co/d/04j2AT9n to get your copy today.”